Libya’s oil industry falls hostage again to politics

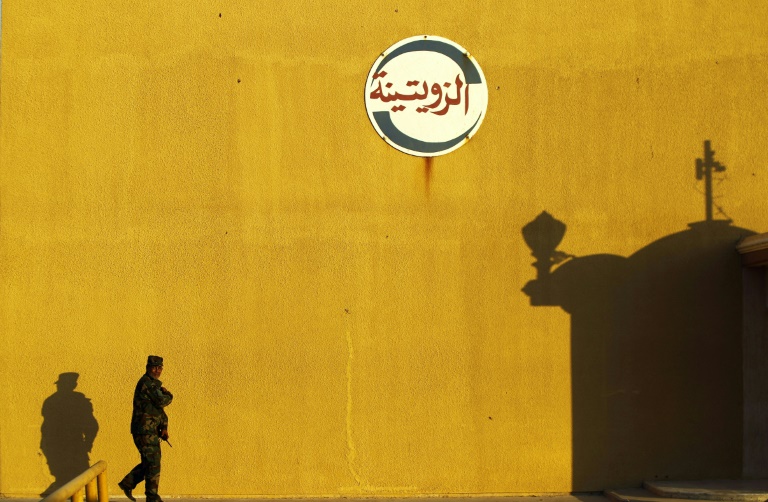

A member of forces opposed to Libya’s unity government walks at the Zueitina oil terminal

Tripoli – Libya’s oil industry, the lifeblood of its economy, has fallen hostage once more to a political schism, as the re-emergence of parallel administrations has forced many hydrocarbon facilities to close.

The National Oil Company (NOC) has this week declared a halt to operations at two major oil export terminals and several oilfields, halving output to about 600,000 barrels per day in a country that sits on Africa’s biggest oil reserves.

The latest in a succession of political fissures since the 2011 fall of Moamer Kadhafi cracked open in February, when parliament, based in Libya’s east, selected a new prime minister, ex-interior minister Fathi Bashagha.

That represented a direct challenge to a so-called unity government based in Tripoli and painstakingly stitched together through UN-led talks little more than a year ago.

The prime minister installed in that process, Abdulhamid Dbeibah, has said he will only hand power to an elected administration, but polls that were meant to take place in December have been indefinitely shelved.

Aligned with the eastern camp, the groups disrupting oil facilities want power transferred to Bashagha.

He in turn is backed by Khalifa Haftar, the eastern military strongman who led a failed bid to seize Tripoli in 2019-20 and who maintains control of several oil installations.

“The closure of oilfields is a direct manifestation of the acute political crisis playing out at the moment between the pro-Haftar camp and the pro-Dbeibah camp,” said Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya researcher.

The high command of Haftar and his allies has “deliberately orchestrated an oil blockade with the goal of heightening Western pressure on Dbeibah” to quit, he said.

– Russia connection –

The oil manoeuvres in Libya come as oil and gas prices have spiked due to hydrocarbon-rich Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has left European governments in particular keen to diversify their supplies and desperate for lower costs.

The shutdowns in Libya further squeeze global supply and represent an additional source of upward pressure for prices — and Russia figures prominently among Haftar’s military backers.

Hamish Kinnear, an analyst at Verisk Maplecroft, sees Haftar’s move as a “blunt method for exerting economic pressure” on Dbeibah’s government, in an attempt to force its resignation.

But Dbeibah on Tuesday reiterated his consistent line that he will only step aside for an elected successor.

He also ordered the prosecutor general to open an investigation into the oil blockades.

Haftar’s strategy is not new — his forces had previously blockaded oilfields in early 2020, but the failure of his offensive against Tripoli months later forced him to end the blockade.

That episode resulted in around $10 billion of losses for Libya’s oil industry.

– ‘Spark’ –

The “spark” that set off Libya’s latest oil crisis was an April 13 “agreement concluded between the NOC and Dbeibah’s government”, Harchaoui said.

That agreement involved the transfer of “$8 billion” of oil revenues to the Tripoli government’s coffers, he explained.

For the newly emergent parallel government, this amounts to a “deliberate waste of public money”, misdirected to feed narrow political and personal appetites.

The NOC made the agreement on the basis that it would “receive emergency funding allocations from the finance ministry for its operations in return,” Kinnear said.

Harchaoui noted that “this exchange of courtesies was seen as having strengthened Dbeibah’s financial viability”.

Consequently, “Haftar and his supporters want to suffocate” his government to the point it collapses in ruin.

On Tuesday, US ambassador to Libya Richard Norland and a Treasury official warned the governor of Libya’s central bank against using oil revenues for “political” ends, according to Washington’s embassy in Tripoli.

With so much attention focused on Ukraine, the risk of a new conflict in Libya appears to be intensifying.

“It is still possible that we will see a peaceful transition,” said Harchaoui.

“But looking at the speed with which Haftar is losing patience, we are also in a situation which could easily degenerate.”