Fears for remains of Jerusalem’s lost Mughrabi quarter

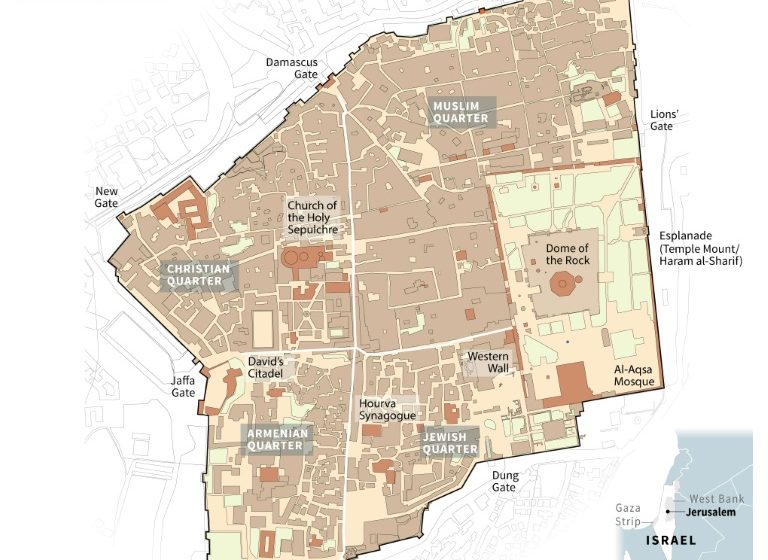

Map of the Old City of Jerusalem

Jerusalem – At Jerusalem’s Western Wall plaza, a recent excavation has alarmed some heritage specialists who fear the traces of a centuries-old Arab neighbourhood razed by Israel may disappear.

There are no signs on the expansive plaza to recall the history of the Mughrabi neighbourhood, or Moroccan quarter, which was demolished by Israeli forces after they captured east Jerusalem in the 1967 Six-Day War.

The area now bustles with tourists and worshippers who cross the stone square to the Western Wall, which marks the holiest site where Jews can pray.

The only indication of its North African heritage is a Moroccan flag, flying discreetly in a nearby private garden.

Last month, excavations which the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) said aimed “to strengthen, stabilise and improve infrastructure” at the site “revealed parts” of the Mughrabi quarter and uncovered the remains of homes.

French historian Vincent Lemire said the discoveries included walls nearly a metre high, traces of paint, a cobbled courtyard and a system to drain rainwater.

“No one expected to discover so many remains of the Mughrabi quarter, so well preserved,” said Lemire, who has authored a book about the neighbourhood’s destruction.

For a brief time, “we could literally walk in the middle of the ancient Mughrabi quarter — in its streets, in its courtyards, in its houses,” said Lemire, who also heads Jerusalem’s French Research Centre.

Within days, AFP journalists saw that some stone remains appeared to have been removed and the area was covered up once more.

– ‘Deeply concerned’ –

The district was initially founded in the 12th century by Saladin, who defeated the Crusader kingdom in Jerusalem.

It was established for Muslim pilgrims from North Africa as it stood below the Al-Aqsa mosque, the third-holiest site in Islam.

The mosque compound is above the Western Wall and is also holy to Jews, who refer to the site as the Temple Mount.

After Israeli forces seized east Jerusalem and its Old City in June 1967, Mughrabi residents were forcibly evicted and the neighbourhood was demolished overnight.

“From previous archaeological activities in the Old City and its surroundings, we are deeply concerned” about the recent findings, said Alon Arad, director of Israeli organisation Emek Shaveh, which fights against the politicisation of archaeology.

He said the IAA’s priority was to create a vast archaeological site which celebrates only the Jewish heritage of Jerusalem.

The IAA has been involved in numerous controversial digs in east Jerusalem, which Israel annexed years after the 1967 war.

Among them are excavations in a Jewish settlement area in the Palestinian neighbourhood of Silwan, just beyond the Old City walls, and tunnels beneath the Western Wall plaza.

The tunnels are now a vast museum displaying ruins dating to the time of the Second Temple, which the Romans destroyed in 70 AD, leaving only the Western Wall standing.

The 1996 public opening of the tunnels sparked violent clashes between Israeli security forces and Palestinians that killed more than 80 people.

Palestinians fear their use threatens the foundations of Al-Aqsa mosque.

– ‘Lost forever’ –

Arad accused Israeli authorities of “silencing any other heritage or cultural affiliation” and of using excavations for the “Judaisation” of the Old City.

The IAA disputed Arad’s claims as baseless, telling AFP that it works on “all the antiquities of Jerusalem, from all the cultures and religions that lived in the holy city”.

The remains discovered last month are too recent to be considered antiquities, the IAA said, but the findings were documented and details would be published in a scientific journal.

The body did not respond to an AFP question about a potential public display.

Morocco, which revived relations with Israel in 2020, “seeks to promote ‘intangible Judeo-Moroccan heritage’,” said Ali Bouabid from the North African country’s Abderrahim Bouabid foundation think tank.

“It’s a strange contrast: when one celebrates diversity loudly, while in silence the other organises its disappearance,” Bouabid told AFP.

Visitors to the plaza are invited to pray at the Western Wall or explore the tunnels, where they can “touch the true stones which recount the history of the Jewish nation”.

There is no mention of the residents who lived for centuries in the site’s shadow.

But the recent dig also unearthed everyday objects such as toys, tools and cooking utensils.

Exhibiting such items could serve as a testament to the “ordinary history of this extraordinary neighbourhood”, said Lemire, suggesting some building remains could be “preserved, displayed and highlighted in a tourist route”.

“If these final remnants are destroyed in the end, the material traces of this history will be lost forever,” he said.