Iraqi Kurds keep nervous eye on Turkish elections

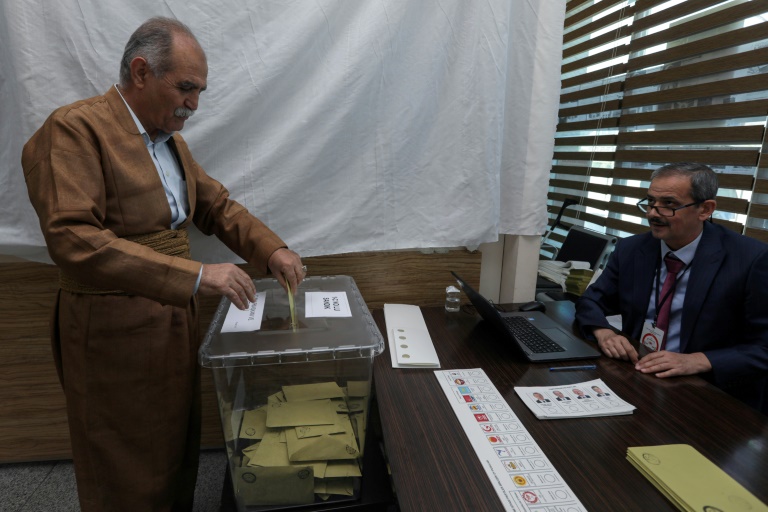

A Turkish citizen living in Arbil, the capital of the autonomous Kurdish region of northern Iraq, casts his ballot for the presidential and parliamentary elections, at the Turkish embassy

Erbil – As Turkey’s presidential vote nears, Iraqi Kurds are keeping a close watch on the tightest electoral battle yet for Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the outcome of which could have major security and economic implications for their region.

For many years, fighting between Turkey’s armed forces and Kurdish militants has spilled over into Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish north, a rugged mountain region where both sides operate military bases.

Many Kurds in war-scarred Iraq sympathise with the ethnic minority in Turkey, but their own region also relies on the big neighbour for business, with its crucial oil long exported via a pipeline that runs through Turkey.

Political leaders in Erbil are not officially commenting on Turkey’s tight electoral race between Erdogan and his challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who has pledged to “bring democracy to this country by changing the one-man regime”.

But, whatever the outcome of the Turkish presidential vote, with the first round to be held Sunday, Iraq’s Kurdish region will look to preserve its strategic partnership with Ankara, analysts say.

“The media, the political scene, everyone is highly preoccupied with the Turkish elections,” said Adel Bakawan, director of the French Centre for Research on Iraq, who stressed that Ankara’s role in the region is “fundamental”.

Iraq’s Kurdish leaders have built relationships with Erdogan, he said, adding that, if “the president changes, the whole relationship between Erbil and Ankara changes… The diplomatic world hates the unknown.”

– ‘Direction of the war’ –

Erdogan, after two decades in power as premier and then president, has strengthened Turkey as a regional player that at times challenges Europe and the United States and negotiates with Russia on Syria’s war.

When he first took office, Erdogan launched talks aimed at ending the Kurdish armed struggle for broader autonomy in Turkey’s southeast. But the community, estimated to be 15 to 20 million strong, came under pressure when those talks collapsed, and violence resumed in 2015.

Turkey’s battle against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), classified as a “terrorist” group by Ankara and its Western allies, has long since flared again across its borders into Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Turkish military maintains dozens of bases in northern Iraq and carries out air strikes and ground operations against the PKK, which operates rear bases in the region.

Iraq’s regional Kurdish government rarely rebukes Ankara, despite Turkey routinely bombarding its territory and causing civilian casualties. Instead, Erbil usually limits its public response to press releases condemning violations of Iraq’s sovereignty and their impacts on the population.

Kilicdaroglu, while making no concrete proposals to resolve Turkey’s Kurdish question, has accused Erdogan of “stigmatising” Kurds.

He has also pledged to free the Kurdish leader of the left-wing Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), Selahattin Demirtas, who has been incarcerated since 2016 for spreading “terrorist propaganda”.

According to Bakawan, given the gestures Kilicdaroglu has already made to the Kurdish community, there is “the possibility of appeasement” in the conflict should he win.

“The result of the election will directly impact the direction of this war,” said Bakawan, a French-Iraqi political scientist of Kurdish origin.

– ‘Betting on relaxation’ –

Political scientist Botan Tahseen argued that Turkey’s opposition is “betting on relaxation” and wants “to turn a new page” after Erdogan, at a time when the Middle East is thirsty for “political, security and economic stability”.

If Erdogan is re-elected, he added, Turkey will still “need an initiative to normalise its relations with its neighbours, especially (Iraqi) Kurdistan”.

Ankara remains a strategic economic partner to Erbil. For years, all of Kurdistan’s oil exports — some 450,000 barrels per day — were sent to Turkey, without the approval of Iraq’s federal government.

A legal dispute between Baghdad and Ankara interrupted the trade, but it is expected to resume once technical and financial details are settled.

“Whoever governs in Ankara will obviously have an influence on this issue,” said Bakawan.

Illustrating the close ties between Ankara and Erbil, a Turkish HDP parliamentarian was on Sunday turned away from Erbil’s airport, local media reported. The provincial government later explained he had been subject to a Baghdad-issued “travel ban”.

For Iraq’s Kurds, notions of ethnic solidarity and hopes for an end to discrimination of Kurds in Turkey are tempered with caution.

“We hope that the next Turkish government will sit down at the dialogue table with the Kurds,” said Nizar Soltan, 60, who works at a university in Erbil.

“Dozens of times they tricked the Kurds and used them to achieve their ends,” he said, sitting in a cafe, complaining that the minority invariably ends up being “marginalised”.

“This time let’s hope they keep their promises, and that the Kurdish regions will regain security and stability.”